If you’re like the vast majority of students, you probably have a hard time memorizing music. For almost everyone, memorizing should not be difficult or frustrating. That’s right, memorizing music, or anything else for that matter, is only hard if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Walter Gieseking was a well known 20th century pianist who was said to be able to memorize entire piano concertos (usually over 30 minutes of music) on a plane flight. Was what Gieseking did magical and unexplainable? The answer is no. Science can explain how it was possible, and even make it accessible to other pianists.

As you read this article you’ll understand exactly how Gieseking and other major pianists are able to memorize music at a super human rate. It does take patience and diligence, but if you follow these steps, I promise you’ll not only memorize music 5 times faster than you are now, but music will be so well memorized you’ll never have a memory slip again, yes never. Not convinced? Read on!

How Memory Works

Memory can be divided into two different types, short term and long term.

Short Term Memory

It’s been very well researched that your brain can remember around 7 “items” (plus or minus a couple) immediately, and that these items are stored in short term memory. Let’s test it out. Below you’ll find my phone number without the area code. Read it once, and then close your eyes and try to repeat it. Here we go. No cheating!

584-3354

Were you able to repeat it? Odds are you were, not hard at all right? Now we’ll try a number that’s a little longer, how about a fake credit card number. Same rules: read it once, close your eyes, and try to repeat it. Here we go!

3859 0375 9136 2849

So how did it go? You most likely failed miserably. Not only could you not do it, but odds are you couldn’t even remember the first 7 numbers. What changed? Most people realize that it’s because 16 numbers are too much to memorize in one try.

So how would you memorize that credit card number? Break it up into smaller groups of course. Everyone does this instinctively. Scientists call it “chunking”. Realizing how your brain works makes this much more meaningful.

How to improve short term memory

So can you improve short term memory and put more than 7 “items” in it? The short answer is no. That’s right, it’s impossible. No one, including Mozart, and the most famed memory experts anywhere have ever put significantly more than 7 “items” in their short term memory. It’s not hopeless though! There’s a trick to it. The trick can make memorizing music, or anything else for that matter, easy. You’ll be able to perform memory feats that seem impossible.

Let’s try another experiment. Below you’ll see a sentence. I want you to read it once and then close your eyes and repeat it.

My dog’s name is Fido, and he likes playing at the park.

Did you repeat it perfectly? I bet you did. But wait, there are 12 words in that sentence. How did you do it if your short term memory can only hold about 7 “items”? The answer is simple. You didn’t have to memorize each individual word because you have associations built from your experiences that grouped certain ideas into one item.

For example, “Fido” is a name people often use for dogs so “dog’s name is Fido” was only one item for your mind. It was an idea that was easy for you to understand because you’ve already made that association. Dog’s play at the park, so “playing at the park” was just another item for your short term memory. The other words “and”, “My”, and “he” are common language constructs that you understand must go between the ideas to make the sentence grammatically correct. So in reality you didn’t have to memorize 12 words, but just 3 ideas. Three items fit perfectly well in the 7 “item” limit of your short term memory, so it was simple to memorize the sentence upon one reading.

Let’s take this one step further. With the sentence above you actually didn’t memorize just 12 words, you actually memorized 42 letters. Yes, you just put 42 things in your short term memory. It was all made possible because you have made associations such as language constructs, spelling, and dogs and parks. This let you group 42 things into just three things. Pretty impressive right? What if you were able to do this with more things in life other than a random sentence. How would this affect learning music?

Duration of Short Term Memory

By now you most likely forgot that phone number from earlier in the article. Short term memory is exactly that, short term. It usually lasts no more than a few seconds. If you still remember the phone number, it’s probably because you repeated it a couple of times. Repetition is the primary way we use to remember things. The more times you repeat something, the more likely you are to remember it. More on this later.

Long Term Memory

Long term memory doesn’t have the same restraints that short term memory has. Science has yet to find a limit to the capacity of long term memory. Have you ever thought that you forget things because you just have too much in your head already? Well that’s not why. Barring disease or brain damage, everyone’s memory capacity is unlimited. Almost always when we “forget” something, it isn’t because it’s no longer stored in our brains, we just may have an inability to access the information. For the purpose of this article I won’t go much deeper into why we forget. If you’re interested in learning more, check out the book “Your Memory: How It Works and How to Improve It”.

So unlike short term memory, long term memory has an unlimited capacity, and potentially unlimited duration. Can you remember the address of your home growing up? What about the phone number for your best friend from elementary school? A lot of people can remember some pretty obscure facts from decades in their past. This is all thanks to your long term memory. With things that we would like to remember, our goal should be to put them in our long term memory.

Photographic Memory

You’ve heard of it. Geniuses have a photographic memory, meaning they can look at something once and take a picture of it in their heads and they’ll never forget. Science has yet to find someone who has it in the way you think it exists.

Sometimes photographic memory is confused with eiditic memory. This is the ability that is found in some children to recall information very vividly in their minds eye for a few minutes. It is almost non existent in adults.

The cases where the popularized concept of photographic memory exist are almost 0. Most of the time memories are misclassified as “photographic” because the person has an abundance of associations made with the subject matter being memorized. Think of it for a second, to an alien who has never heard of a written language, wouldn’t memorizing 42 letters at first glance with the sentence above be considered “photographic”? Somehow on first glance you were able to recall 42 separate items. In the same way, most people are confused when someone does an incredible memory feat, so we label them as having a photographic memory.

Memory Techniques

Now that you have a basic understanding of how memory works, we need to look at how to get the important things into our long term memory.

Repetition

This is the most effective way to memorize. The key is to make sure you’re not doing the repetitions mindlessly. Try memorizing a credit card number by repeating all 16 numbers over and over and over again. It will take you a very long time to get those numbers memorized. The reason is because of your short term memory capacity. After the first 7 “items” your short term memory gives up and mentally you probably get frustrated. You may even say to yourself “This is impossible”. We all know that memorizing 16 numbers isn’t too hard though. All you have to do is break them into groups. Start with the first 8 or even the first four numbers. Repeat those numbers maybe 10 times. Then start with the next group. After a very short amount of time you’ll have all 16 numbers memorized. The key to successful repetition is to only repeat what you can remember after ONE look. If you can’t remember the first 8 numbers after reading them once, then it’s too much for your short term memory and you need to take a smaller group.

Active Recall

You must actively try to retrieve the information you are memorizing as opposed to passively reciting it. In academia, often review material will ask the student to answer questions about the text they are reading. This is active recall. If you’re just reading information, even repeating it, you are passively recalling the information which is far less helpful. Creating associations with information is a great way to practice active recall as well. More on this later.

Sleep

Some people spend way too long trying to memorize one thing. Once they feel fairly comfortable they’ll move on. This can cause frustration. When you have done quite a few repetitions you should be done for the day. Don’t spend hours repeating a small section. You don’t have to go back the same day and check if it’s still memorized either. Sleep will do all of this for you. It’s almost magical, but by sleeping your brain solidifies everything you tried to memorize that day. Scientists call this consolidation. Some of the information that you memorize will become more stable the next day, and some will become less stable just because of the passing of time. If you do the same process of repetition the following few days, each night of sleep will continue to consolidate your memories, and eventually what you are memorizing will be firmly stable in your long term memory.

So am I just basically saying come back to it the next day? YES! Isn’t this obvious? You must realize what is important here is that you don’t need to work on memorizing one small section all day long. Spend just a little time on it, and move on!

Naps

Studies show that naps can have a similar effect on memory as a full night’s sleep. Memorizing something followed by a nap, and then more memorization can be very effective. The nap in between can replace the consolidation that is needed with sleep at night, effectively doubling your learning time. Remember though, you could also just as easily memorize more during the day and have it consolidate at night, with the same net effect. This kind of learning is most helpful if you only need to memorize a small amount of information very quickly.

Does Cramming Work?

Of course not. Well, sort of. Teachers and parents say not to do it, but why do students ace tests by cramming then? They are using repetition to put information into a state between long and short term memory. After one night of sleep most is still memorized, but since the test has already been taken, almost no students study the information again, and it goes from that limbo state out of the students memory completely. A few days later the student will almost always have almost no ability to recall any of the information they put on the test just a few days earlier. Learning by sleeping is essential to having something memorized well.

Spaced Repetition

What is it? Basically studying material over a long period of time. The opposite of cramming. Repeating something over and over again for a couple of days isn’t going to do it. This goes back to why sleep is important, but even beyond sleeping, material needs to be reviewed often in the future. Learning it once and then setting it aside is not going to do it.

The steps to memorizing can be broken down as follows:

- Put information into short term memory

- Repeat the information in your short term memory multiple times

- Sleep

- Repeat steps 1 through 3

- Do the whole process again after some time has passed.

After a few days the information being memorized will be solid. Very solid. That doesn’t mean put it aside forever though. Remember spaced repetition. You’ll need to come back to the material at regular intervals for an extended period of time to get the full benefit.

How Does All of this Apply to Music?

If you’re still with me, you probably already know the answer to that. I want to go over specifically how to apply this to learning music though. I’m going to use the piano as an example because pianists have quite a bit of music to memorize, but these techniques can be applied to learning music on any instrument, even voice.

Memorize First and Always

Do you learn a piece of music from the beginning to end and then start memorizing it? That’s a complete waste of time, always. If the piece needs to be memorized, why learn the whole thing twice? It honestly doesn’t make any sense. Teachers should require that they only hear music in lessons that is memorized. Sight reading practice is obviously an exception, but if a piece is to be memorized, it should be memorized from the beginning.

Memorizing with Associations

So how did Gieseking learn an entire piano concerto on a plane flight, and play it the next day? The answer is associations. The same way that you could memorize the dog sentence from earlier, Gieseking could memorize music. In order to memorize music quicker you must find patterns, groups of notes that make sense as a group, and commit them to short term memory and then repeat. Let me give you an example:

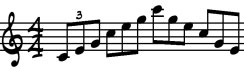

To the uneducated musician the picture above may look like a bunch of individual notes. If we count, there are 12 notes in that section. If you had to memorize each note individually, the best way to memorize this is breaking it up into two small sections of 6 notes and repeating each section multiple times. If you involve your brain a little though, you’ll find there is a much easier way to do this.

As you can see in the picture above the two red boxes have the same notes in them. So if you memorize the first six notes you have already memorized the last six. If we took it one step further, this group of notes is called an “arpeggio”, if you recognize it as an arpeggio then there is only one thing to memorize. Just by looking at it you could repeat it today, tomorrow, and next year, because you already committed what an arpeggio is to memory long ago.

That was a pretty simplistic example, but hopefully you understand the point. Patterns are everywhere in music. It’s your job to find them, and then your teacher can help you label them. Once you have labels for these different patterns, you have built a new association. Next time you see something resembling that pattern in different music you will recognize it for what it is, and it will represent just one item in your short term memory. This is how Gieseking was able to perform super human feats. He had made so many associations within music already that he could probably fit half a page in his short term memory. This significantly shortens the time it takes to memorize a piece of music.

If you learn music without this method, you will succeed in just learning the piece you’re working on. You may grow musically and technically, but it will not give you the ability to memorize other pieces faster. If you memorize music by making associations, you will find these associations in all future music that you play. Every association you make will increase the speed you learn music and your ability to recognize patterns.

Notice I haven’t spoken much about “Music Theory”. Music theory is just the study of music. People put labels on certain patterns of notes and how they work together, and we call it music theory. I personally don’t believe in spending a lot of time learning music theory independently. I believe it should all be learned within the context of music. Once a pattern is recognized a good teacher should point it out and explain what it means in the context of the music. This is when the teacher should explain what a chord is, or an arpeggio, or a key. When music theory is taught out of context and in a book, it is easily forgotten and almost never understood.

Memorize Small Sections or SMALL Sections

You have probably been told to memorize small sections at a time. That’s good advice. Some teachers might say to start with a phrase or a couple measures. That’s incomplete advice. The goal shouldn’t be to work on some predefined section. You should only work on repeating music that can fit in your short term memory. If you can only fit two beats of music, or even just one beat, then that’s what you repeat.

The way to figure out what can fit in your short term memory is simple. Read it once then close the book or look away, and try to repeat it from memory. If you can’t, then it’s too much. You’ll need to take out a couple notes and then try again.

Remember that your first step shouldn’t be to pick some random section. It is first to look for patterns and associations, once you find them, find out how much you can keep in your short term memory and repeat.

Never Forget About Sleep!

If you are getting bored repeating a section over and over again, move on. Sleep is the best thing you can do for your memory. Repeat a section maybe 10 times then move on, and don’t go back to it. Do the same thing the next day with the same section. After two or three days it will be memorized. Too many students waste hours practicing sections that will never get any better in one sitting. In this way you can work on a lot more music without wasting your precious practice time.

Spaced Repetitions

Always remember just because a piece is memorized, doesn’t mean it will be forever. Spaced repetitions often come naturally for musicians because we often play the same memorized piece for quite a while, in auditions, recitals and competitions.

Don’t forget though that repetition is still important months after a piece is initially committed to memory. After a long period of time has passed with you actively recalling the music (not just playing by muscle memory) the piece will be even more entrenched. Try writing the piece of music out, or playing it away from the piano. This (and reviewing associations you have made) will aid in memorizing and active recall.

The Lie – Muscle Memory

Most young pianists memorize pieces with just what some people call “muscle memory” meaning you turn your brain off and your fingers just find the right notes. This kind of memory will happen regardless of your effort when you play something enough times.

“Muscle memory” is not even memory, it’s purely habit. Habits are formed in the most primitive parts of our brains. Studies have shown that people with no ability to form new memories, because of accidents or disease, are still able to form new habits. This shows that habits are not technically memories. When musicians depend on “muscle memory” what they really are doing is repeating patterns mindlessly.

This type of “memory” is also very prone to memory slips because the music is actually not in the musicians memory at all, and any small break from the habit (like a mistake or someone in the audience coughing) can cause the habit to break down.

Real music comes from our actively engaged minds. If the musician cannot sit down and write out an entire piece of music from memory, the piece is not memorized. Never try to acquire “finger memory”. It will come naturally because of constant repetitions. You should always seek an intellectual understanding and memory of the music first.

Quality and Speed

The greatest part about this way of learning is the quality that the music is learned. Because you are focusing on such a ridiculously small section of music you can be cognizant on how it should actually sound. Yes you can care about the articulation, the dynamics, your touch, fingerings and everything else that your teacher constantly tells you to pay attention to. The problem is most students have such problems with just learning the notes that all of the important specifics that actually make music sound good are forgotten. Always memorize everything the first time. By the time you get to the end of the piece, it will be completely memorized and performance ready. There will never be any need to go back and memorize it, or go back and add dynamics, or anything else. It was learned right the first time. Because of this you’ll find yourself learning music literally 5 times faster than you ever did before. The biggest difference though will be that it will actually sound good.

Conclusion

The results from making these changes in your practice routine are significant. Test it out for yourself. We’re trying using it with students who take piano lessons at HBSM. These aren’t just a few tips you should maybe use. This is science, and it works.

Brian Jenkins